Contesting the ‘New Japan’: Rethinking Japanese Interwar Politics (1919-1941)

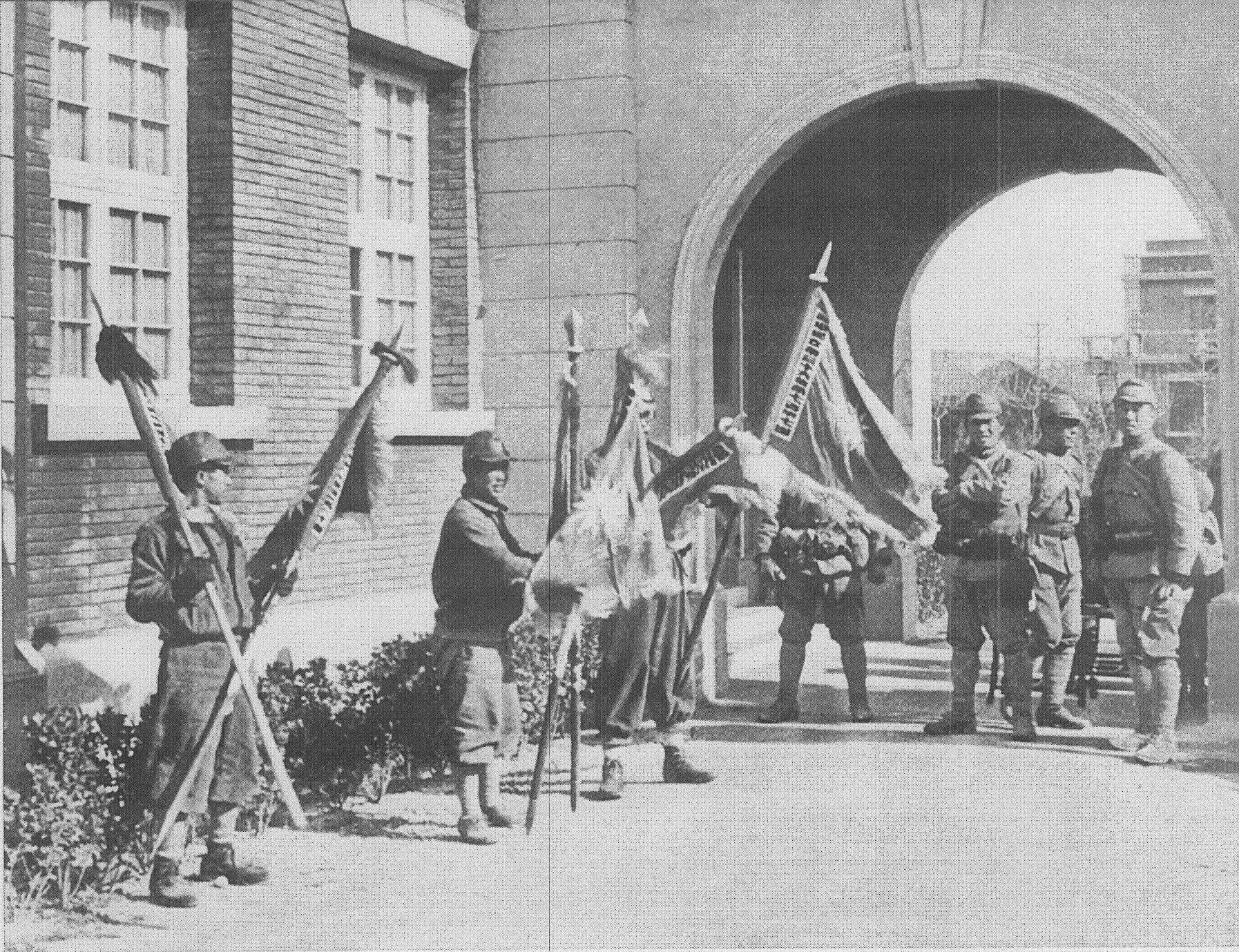

Pictured: War Flags of China obtained by Japanese forces in Nanking, December 14, 1937, Asahi Shimbun, China Incident Photograph Album Volume 2 (Shina Jihen Shashin Zenshu Vol. 2), (1938), obtained from Wikimedia Commons, April 26, 2008.

Introduction

Our adversaries, showing not the least spirit of conciliation, have unduly delayed a settlement; and in the meantime they have intensified the economic and political pressure to compel thereby Our Empire to submission. This trend of affairs, would, if left unchecked, not only nullify Our Empire’s efforts of many years for the sake of the stabilization of East Asia, but also endanger the very existence of Our nation. The situation being such as it is, Our Empire, for its existence and self-defense has no other recourse but to appeal to arms and to crush every obstacle in its path.

With the delivery of the Imperial Proclamation of War on December 8, 1941, the Japanese nation formally embarked on a new stage of its conflict against the “adversaries” which, in the eyes of the government and military, had worked to prevent their nation’s rightful ascent to becoming the dominant regional power in Asia. Three days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Imperial General Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference deliberated on what to call their latest escalation of hostilities against Great Britain and the United States. Much like the post-war historiography, the debate over nomenclature revolved around two key dimensions: the war’s geography and purpose. Whilst the Imperial Japanese Navy preferred to emphasize the former (i.e. the Pacific War), and several ministers the latter (i.e. the War for the Development of Asia), the conference finally settled on a title which compromised between the two principles, declaring that “the latest war against the United States and Britain and war that may arise depending on future developments of the situation, including the China Incident, shall be named Greater East Asia War.” In the same conference, Tokyo declared that “the demarcation point between wartime and peacetime shall be 1:30 a.m. on December 8, 1941.” In February of 1942, the cabinet adopted Act No. 9, which decreed that any current or future laws which made reference to the “China Incident” would henceforth be altered to reflect the new name of the war, which had widened beyond the Chinese mainland.

Ever since the conclusion of the Greater East Asia War on September 2, 1945, historians have grappled with the challenges posed by both the official and unofficial names for the conflict, which some have viewed as a continuation of the Second-Sino Japanese War, and others as the ultimate stage in a “Fifteen Years’ War” beginning from the Manchurian Incident in 1931. Indeed, although the vast majority of works in English on the period clearly delineate between the naval theatres of the Pacific and the land-based military operations in China, there is some value in questioning the need for a clear boundary between the two. Though militarily, there may have been little overlap between the two wars, both represented the multi-faceted aims of Japanese strategy, which had developed in the pre-war years and would continue to be altered as the fighting progressed. Alessio Patalano, in reviewing the unity – or lack thereof – in that strategy, clearly illustrates just how interconnected and diverse these aims were:

[The] diversity in ideas [about the purpose of the Greater East Asia War] strengthened the argument that from 1937 to 1945, the Japanese fought different types of war, some simultaneously, others in a close sequence, and also conceptualized them as separated in strategic terms…For the Japanese, the expansion of military operations in East Asia from 1937 to 1945 had multiple dimensions; they were regional and global; they fashioned ambitions of colonial expansion and imperial defence. The debates concerning the right name for the conflict were rooted in the political implications of a conflict with multiple dimensions.

The implications inherent within the debate over the nomenclature of the war – aside from posing an interesting question for aspiring writers of the conflict(s) – serves as a point of departure for wider queries about Japanese interwar history. Orthodox narratives of the interwar period in Japan tend to portray 1931 as a “turning point” for Japanese politics, with the invasion of Manchuria marking the end of Japan’s cooperation with the international community and its simultaneous turn towards exclusive empire in Asia. At the domestic level, these accounts portray the 1930s as a descent into the so-called “Dark Valley,” characterized by authoritarian and fascistic governance by right-wing bureaucrats alongside the military. Yet as the contemporary debate over the nomenclature of Japan’s conflicts shows, the danger of this orthodox historiography is that it sets the foundation for a teleological reading of Japanese interwar policymaking. Agency and contingency are sidelined in this historiographical approach, and the descent to war in 1941 presents itself as the inevitable climax of earlier conflicts in Manchuria (1931) and China (1937).

However, by questioning this orthodox framework and expanding the chronological boundaries of an investigation, a more nuanced and complicated picture of the interwar period emerges. In other words, if one wishes to view Japan’s series of “Incidents” and wars in the 1930s and ’40s as part of a larger narrative of expansion and security-seeking, then a whole host of questions arise over which of the specific lenses to use, and what interpretations those viewpoints lend themselves to. Can we, for example, continue to portray 1931 as a “turning point” for Japanese politics and policy in the same way 1930 provides a convenient line of demarcation for events in Europe and the Americas? Are there individuals who deserve special mentions for their contributions to Japan’s domestic and foreign policies – or even those who led the nation towards war? Can the socio-political changes which took place during the 1930s be classified as the fascistic descent into the “Dark Valley” that it has been? The importance of addressing these questions in any treatment of Japanese interwar political history is critical to shaping the overall narrative. Divergences in answering them have led one historian to portray the transition between the 1920s and ’30s as one in which Japan’s leaders “chose emperor and empire over democracy,” and another to argue that the prosperity of the democratic Taishō (1912-1926) period preluded the authoritarianism and violence of the Shōwa.

This review article is intended to be a survey of those historiographical questions in interwar Japanese politics, focusing on the 22 years between the end of the First World War and the Pearl Harbor attack. Rather than treat the socio-political developments of the Taishō and Shōwa eras as two distinctly separate timeframes, it argues that such a division is arbitrary and restricts a thorough investigation of continuity – or indeed discontinuity – between the party politics of the 1920s and the militarism of the 1930s. In doing so, this article complements Frederick Dickinson’s writing on the interwar periods, echoing his call to “view the interwar years as an era of remarkable opportunity.” Similar to Dickinson’s study, the approach here will be thematic as well as chronological, analyzing aspects such as the role of the military, foreign policy, and economic security throughout the period in question. As we shall see, interwar Japanese politics is a topic rife with historiographical potholes and interconnecting strands of investigations. Conducting a study in this field is akin to treading a narrow path: one must avoid the temptations of reductionism and fatalism in order to strike a scholarly balance. In much the same way that Japan’s wartime leaders debated which of the multi-faceted aims of their war should take primacy in the nomenclature, historians should be wary of writing narratives that easily lend themselves to convenient binaries and teleologies.

Pictured: A scene of an Imperial General Headquarters meeting, 29 April 1943. Showa Emperor Hirohito is in the center. Navy officers are seated left while Army officers are seated right, Asahi Shimbun, (1971), obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

The View from the Peaks: Framing Japan’s Interwar Years

Viewed from the death and destruction of the Second World War, Japan’s turn towards right-wing ultranationalism and militarism in the 1930s can be argued to be symptomatic of the interwar crisis period that engulfed the world following the Great Depression and the collapse of collective security. Set against the backdrop of the country’s rapid modernization and international rise during the late nineteenth century, the interwar years appear as a period of great uncertainty, one which witnessed the political establishments experimenting with democracy whilst retaining older authoritarian elements. It could be argued— if one views the 1920s from the ruins of Imperial Japan in 1945—that the flourishing of party politics during the Taishō emperor’s reign was an aberration that resulted from the postwar wave of modernization and liberal internationalism that swept through the country. In this light, the triumph of militarism and ultranationalism during the Shōwa period appears as a return to the authoritarian governance which characterized the Meiji era, a reversion destined to occur once the initial enthusiasm for democracy had been stamped out in the wake of the Great Depression.

These interpretations, whilst once a popular way to view Japan’s course during the interwar period, have been challenged in recent writings. Elise Tipton has highlighted that Japan in the 1920s presents a “complex, contradictory, and multivalent” picture and that the question of what exactly constituted a “modern” state spurred all manner of intellectual musings and ideological writings in the country. There is also an issue with implying a sort of discontinuity between 1920s Japan and 1930s Japan: the former marked by the ascendancy of parliamentarism, the latter by the ascendancy of militarism. If we apply this perspective, then it would seem prudent to deem that the prime ministership of Hamaguchi Osachi (July 1929 – April 1931) and that of Fumimaro Konoe (June 1937 – January 1939) were parallels, with no similarity in either structure, nature, or policy. In effect, those who judge the developments of the 1920s from the vantage point of the 1930s are clouding their own analyses, validating Dickinson’s claim that “the violence of the 1930s has cast a pall over our understanding of 1920s Japan.” Instead, we should view the 1920s in Japan as a time of great opportunity and change, one in which the political elites and masses eagerly sought to partake in. Moreover, the 1930s also did not bear witness to the complete erasure of the democratic parties in favor of fascistic right-wing rule, as Kitaoka Shinichi points out:

[I]t would be a mistake to stress only the discontinuity between the two. The 1930s were born out of the 1920s, and the developments of the 1920s were not only inherited by the 1930s but also passed on to serve as the foundations of Japan’s postwar rebirth. Yet the military was far from impotent during the period of party politics – it was, [in fact], a powerful presence. Nor did the political parties slip into insignificance in the 1930s. Until the end of the decade, as before, they wielded considerable power.

Of course, just as with the rapid modernization of the Meiji era, there remained those who resisted the rise of this “New Japan” after the First World War. These groups sought to challenge the liberal internationalism of the late Taishō period, giving rise to the ideologies and movements which would come to the fore in the early Shōwa years. There was, however, no “collapse” of the “Taishō democracy,” nor was it substituted overnight for a system of “reinforced authoritarian politics” as Andrew Gordon posits. When the Young Officers of the Imperial Japanese Army embarked on their campaign of systematic violence both within and beyond the country, they were not attempting to instigate a complete return to the emperor system of the Meiji era. Instead, they were firing the opening salvos of a new chapter in Japan’s post-World War I search for a national identity and international standing, spurred by domestic and foreign causes which were exacerbated by the Depression. Even within the military during the interwar period, there were fierce disagreements over the future of the Japanese state, represented most prominently in the inter- and intra-service debates on the direction and timing of the empire’s expansion.

What, then, is the case for viewing Japan’s interwar years from the peak of the First World War? Scholars have often preferred to portray the Treaty of Versailles and the decade following the conflict as one of reluctant participation in the “Washington system” of naval treaties and collective security ideals which the League of Nations represented. To be precise, there were disappointments in the peace settlement, which ushered in a new vision of the modern world in Japan and the West – the rejection of the racial equality clause in the League’s Covenant among them. However, cynical interpretations of Japan’s participation in the Paris Peace Conference – that its delegation was merely sent to secure recognition of new imperial acquisitions in China and the South Pacific – ignore contemporary accounts which emphasized Japan’s newfound global position. That Japan had secured a place as one of the “Big Five” powers at the Peace Conference speaks volumes on exactly how crucial the war had been in its elevation from regional to world power status. Japan’s authority, as Prime Minister Hara Takashi put it in Paris, “has gained all the more authority, and her responsibility to the world has become increasingly weighty.”

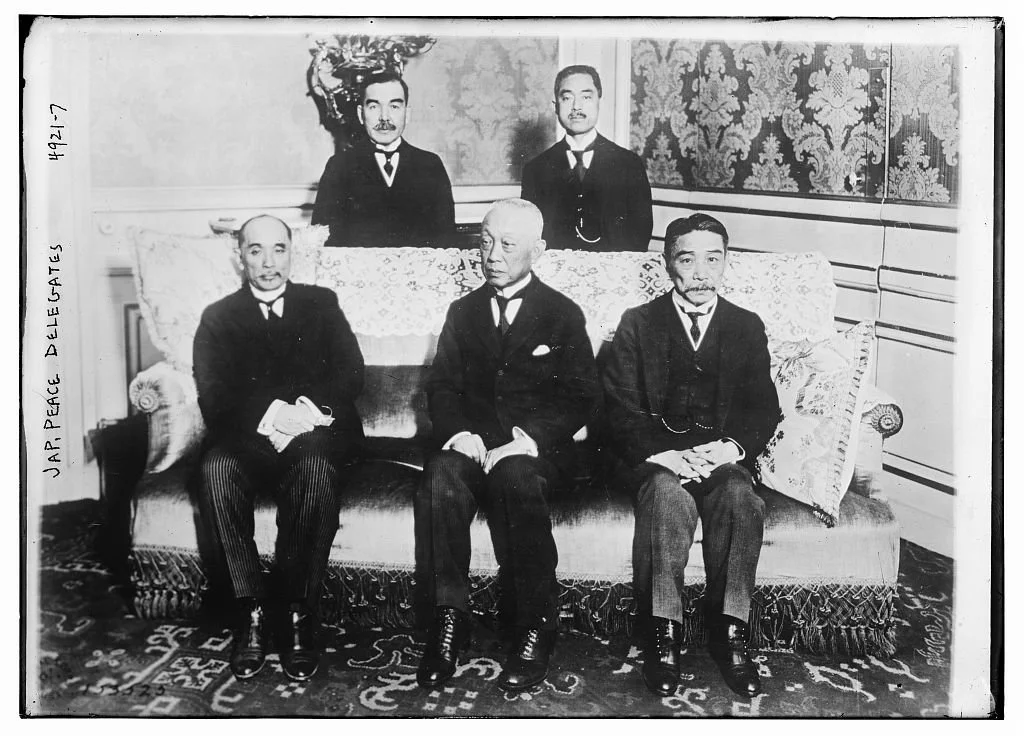

Pictured: Japanese delegates to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, 1 negative: glass; 5 x 7 in. or smaller, Bain News Services, (1920), obtained from Library of Congress

Contemporary news reports on the “responsibility” of Japan to eradicate racial injustice at the Peace Conference also reflected a genuine belief on the part of the general public and the media in Japan’s central role in the transition from imperial to liberal world mechanisms. One article in the Asashi newspaper drew parallels to the British opposition to slavery at the Congress of Vienna more than a century earlier:

Now the question of racial discrimination occupies today precisely the position which that of slavery did then… Japan being the leading colored Power, it falls on her to go forward to fight for the cause of two-thirds of the population of the world. Japan could not fight for a nobler cause… Japan must endeavor to make the Peace Conference leave behind a glorious record of putting an end to an inhuman and anti-civilization practice as did the Vienna Conference a hundred years ago.

Evidently, Japan’s masses were already aware that the foundations of the old world were being swept away, and that their country was now poised to play a role in forging the pillars of the twentieth century’s political and economic modus operandi. Viewed as such, the Taishō period can be subsequently assessed as one in which Japan willingly and enthusiastically participated in the internationalist diplomacy which came to characterize relations in the Asia-Pacific region during the 1920s, embodied particularly by the figure of Foreign Minister Kijūrō Shidehara. In adopting this view, one also becomes cognizant of just how exaggerated opposition to internationalism was during the Taishō period. Confined largely to specific groups within the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and Army (IJA), public and political elites applauded Japan’s cooperation with the West in the naval treaties and the maintenance of the “Open Door” policy in China. Domestically, the Japanese public of the 1920s did not merely experiment with democratic ideals such as universal suffrage and labor rights but took active and enthusiastic steps to champion these progressive ideals within the upper echelons of the political establishments. This was one critical component of the effort to re-mold Japan’s identity in line with the liberal and internationalist zeitgeist of the 1920s.

Thus, it would appear more beneficial to view and assess Japan’s political developments following the First World War as the nation’s response, at all levels and across all groups, to the new vision of modernity and the nation-state of the twentieth century. Just as the arrival of Commodore Perry in 1853 had sparked Japan’s nation-building in an age of empires and imperial competition, the end of the Great War sparked an era of nation-modernizing in a new age of liberalism and international cooperation. As Zara Steiner has wisely advised, “the 1920s must be seen within the context of the aftermath of the Great War and not as the prologue to the 1930s and the outbreak of a new European conflict.” It would seem appropriate, given what has just been discussed, to extend the scope of this advice to those studying the outbreak of a new global conflict, critical as Imperial Japan was to the Asia-Pacific theatre of the Second World War. There was no simple linearity in the path Japan took between the wars, and understanding why collaboration and pluralism gave way to conflict and authoritarianism – though with some degree of continuity – is crucial to comprehend just how dynamic and multi-dimensional Japan’s interwar political landscape was. The next set of questions revolves around the party, which, in most narratives of the interwar years, shoulders the responsibility for the descent into the Dark Valley and the ultimate death of Imperial Japan.

Against the Popular Tide: Military Factionalism in the Interwar Years

The role of the military in Japanese interwar politics is a topic that has fascinated historians since the country’s surrender at the end of the Second World War. With the prosecution of many generals and admirals during the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, it was widely perceived that the military held sole responsibility for dragging the nation towards the war in China and the Pacific. Nowadays, historians have recognized that the military itself was hardly the unified and concerted apparatus that early Cold War narratives propagated. Just like their civilian political counterparts, the military was filled with ideological splinter groups, inter-service rivalries, and intra-service divergences:

Neither the political parties nor the military existed as monolithic entities…within the military, there were divisions between the army and navy; between the Ministry of Army and Army General Staff Office; between the Ministry of Navy and Navy General Staff of Office; and so on – and there were frequent conflicts and contention among and between almost all of them. In addition to the usual bureaucratic rivalries, there were also fierce disagreements over ideology and policy.

Once again, one could trace a line connecting the immediate post-Meiji military with its late Taishō counterpart and argue that the latter was simply an evolution of the former. Certainly, there were similarities to be found between the two in terms of the plurality of ideological and strategic visions. Factionalism was not a wholly new product of the Taishō era disarmament and internationalism, but rather a transition from the hanbatsu (domain-based) cliques to a new gakubatsu (school cliques), where an officer’s fellow students mattered more than their clan background. Here, the web of army politics poses some issues to fully understanding the extent of factionalism within the military, and most popular narratives focus on the two factions which came to the fore in the 1930s: the Tōseiha (Control) and Kōdōha (Imperial Way).

These two factions were far from the only factions which formed during the interwar period, but they were the ones that were recognized by the other officers to be at the forefront of the factional strife amongst some of the army’s top officials. Initially, these factions were concerned with internal questions of army modernization and future strategy, but with the onset of the Great Depression and the perceived ineffectiveness of democratic rule, they became increasingly tangled in the question of the country’s domestic situation and its salvation. In the strenuous and brutal education programs that officers during the late Taishō era had to undergo, they were also indoctrinated with ultranationalist thought. Cadets were often instructed to attend lectures at the Institute for Social Research (Daigakuryo), where notable intellectuals such as Okawa Shumei and Yasuoka Masaatsu discussed the nation’s identity and place in the world. Both Shumei and Masaatsu wrote extensively on Pan-Asianism and espoused the proposition that Japan rightfully deserved to lead the Asian peoples in a struggle against their Western colonial masters. They also questioned whether the kokutai was being weakened as a result of external and internal corruption, which considerably influenced the anti-Western rhetoric of the military and right-wing bureaucrats. The writings of Nishida Mitsugi, one of the key members of the Young Officers’ Movement (Seinen shōkō undo), hint at the growing concern within the officer cadet corps about the apparent “decay” of Japan:

Look around! See what has become of our beloved country… The genrō [political advisor elites] have usurped the powers of the Emperor. The ministers behave in a shameful way. Look at the Diet. Are these the men responsible for the affairs of state? Are these our leaders? Look at the parties which claim that they defend the Constitution! See the so-called educators, businessmen, and artists, and look at the misguided students and the distressed masses… The ruling clique makes the same mistakes in foreign affairs, internal policies, the economy, education, and in military affairs… Party government may be a good idea, but the way it is conducted by our parties is so disgraceful that it has brought Japan to the brink of disaster.

With the political turmoil following the Manchurian Incident and the subsequent invasion, the army factions began to more heavily involve themselves in domestic political violence, with many groups working towards the aim of a “Shōwa restoration.” So frequent and damaging was this violence that the period would come to be known as the era of “government by assassination,” as previously lauded officials who had held office in the 1920s were killed by military personnel who found their policies too liberal, leading to the “decay” of the country’s strength both at home and abroad. Many of these factions, with the key exception of the Tōseiha, endorsed the use of violence to achieve their aims and bring about changes within Japan’s political system. One document from the Sakurakai (Cherry Blossom Society) illustrates such an aim:

[The political leaders] have forgotten basic principles, lack the courage to carry out state policies, and completely neglect the spiritual values that are essential for the ascendancy of the Yamato people. They are wholly preoccupied with their selfish pursuit of political power and material wealth. Above, they veil the sacred light, and below, they deceive the people. The torrent of political corruption has reached its crest… Now, the poisonous sword of the thoroughly degenerate party politicians is being pointed at the military. This was clearly demonstrated in the controversy over the London treaties… It is obvious that the party politicians’ sword, which was used against the navy, will soon be used to reduce the size of the army. Hence, we who constitute the mainstay of the army [officers] must… arouse ourselves and wash out the bowels of the completely decadent politicians.

The climax of army factionalism came during the February 26 Incident of 1936, when elements of the First Division under the leadership of Young Officers staged a coup attempt in Tokyo, declaring their aim of installing a military-led government and waving banners with their slogan Sonno tōkan (Revere the Emperor, destroy the traitors). Though they succeeded in taking over key government offices and paralyzing the rest of the army’s ability to respond quickly, their efforts were dashed when Emperor Hirohito himself refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of their actions, and both the IJN and IJA cooperated – a rare occurrence – to diminish the rebels’ chances of success further. Even with the post-Incident purges and reshuffling of the army command, the army maintained and even increased its influence over the civilian government in several ways, as Meirion and Susie Harries argue:

The [February 26] revolt not only changed the balance of power within the army, it also profoundly altered the balance between the army and its civilian antagonists. At a stroke, the rebels removed several of Japan’s leading proponents of constitutional monarchy, and provided a display of military brute force vicious enough to guarantee the cooperation of others who might otherwise have challenged the army. In the nature of total-war planning, the leaders of the army needed partnership with other technocrats, so the army was never to assume an absolute dictatorship, but direct and overt opposition to its plans ceased after February 1936.

Such was the power of the army and navy over the civilian government that Prime Minister Kōki Hirota – who succeeded the Okada cabinet following the February 26 Incident – remarked to a friend that “the military is like an untamed horse left to run wild. If you try to stop it head-on you’ll get kicked to death. The only hope is to jump on from the side and try to get it under control.” Evidently, the Japanese military of the 1930s was far from the united body of right-wing personnel that orthodox historiography often portrays it to be. It was a fractured entity splintered into various ideological and political ‘camps’, all of whom believed that there was something wrong with the ‘New Japan’ that the 1920s attempted to create, but disagreed over what exactly was corrupting the kokutai and how to purge it of any corruption.

Pictured: Japanese rebel troops returning to their barracks after the failed February 26 coup, 29 February 1936, Chaen Yoshio, Zusetu 2/26 Jiken, Nihon Tosho Center, p. 181, (2001), obtained from Wikipedia Commons.

How, then, are we to view the military within Japanese interwar politics? Firstly, it should be made clear which specific parts of the military we are referring to at each stage of this period. The IJA and IJN on the eve of the Pacific War were far from what they were at the end of the Siberian Intervention politically and militarily, and even within their command structures, there existed factions and disagreements which would impact the overall nature of civil-military relations as Taishō gave way to Shōwa. The Young Officers were not actors in a political vacuum. The intra-factional arguments over national strategy and security shifted as the larger geopolitical situation left Japan isolated and the West became increasingly antagonized by the military. Secondly, we ought to be aware of the key “battlegrounds” that dominated the debates surrounding strategy and expansion in Japan: economic security against imperial expansion, Pan-Asianism against Japanism, and total war against short war.

Moreover, it is clear that any investigation into the military’s role in Japan's policy must also take into account its relationship to domestic changes as well as the international situation. Why, for example, did the Washington system generate less controversy in the Navy than the London Conferences did almost a decade later? How influential were the army reductions of the mid-Taishō years in curbing, or flaming, dissent amongst the officer cadet corps? What changed in the policy papers of the IJA and IJN, and how important were their arguments on the civilian government of the 1920s compared to the 1930s? These are just several questions that highlight the need for multi-dimensional analyses of the military, in addition to Japanese interwar politics as a whole. The next section deals briefly with the key debates over Japan’s foreign policy and strategy, highlighting further the conditions and causes which led to the “Greater East Asia War” in 1941.

Outsider or Challenger? Japanese Strategy, the World, and the Road to War

Our present foreign policy is to establish the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, but the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere is the same as the New Order in East Asia Sphere or the Security Sphere, and its scope includes Southern areas such as the Netherlands Indies and French Indo-China; the three nations of Japan, Manchuria and China are one link.

When Foreign Minister Yosūke Matsuoka proclaimed Japan’s new foreign policy orientation in the summer of 1940, he was not declaring a separate track of Tokyo’s expansion – and in hindsight encroachment – into the “Southern areas” in addition to the ongoing war in China. Rather, the declaration provided a neat continuity from the previously continentalist foreign policy outlook which characterized Japan’s diplomacy from the Manchurian Incident to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. As early as 1936, the new “Fundamentals of National Policy” drafted by the Hirota cabinet hinted at the nation’s gaze turning southwards, with the express belief that “Japan should be the stabilizing power in East Asia nominally and actually.”

Stepping back for a moment, Japan’s imperialist conquests during the 1930s are often portrayed as starkly different from those of the late Meiji and early Taishō periods, both in scale, motivation, and justification. The invasions of Manchuria, China, and the Pacific War were, as Akira Iriye suggests, being increasingly “driven by ideology.” As early as the 1920s, during the period of Japanese cooperation in internationalist diplomacy, conceptions of empire and considerations of economic security were being debated in political and intellectual circles. Perhaps because of the Taishō period’s relative lack of censorship and encouragement of free thought, these ideas were able to circulate without influencing the dominant enthusiasm and preference for cooperation vis-à-vis the West and China. Was economics – or rather economic security – the main engine of expansion? The evidence would certainly suggest that resources and the drive for autarky were prominent reasons for Japanese imperialism in Manchuria and mainland China, and the need for oil was certainly a critical consideration for both the military high command – albeit this was more a concern for the navy – and civilian government. Indeed, both the policy papers of the army and the navy in 1936 emphasized the securing of resources before any mention of cooperation or Pan-Asianist “liberation,” but we must also recognize that the economic reasons for expansion were constantly being re-evaluated in light of geopolitical and domestic developments. Pan-Asianism has often been named as another factor that played into Japanese strategic thinking in the latter half of the 1930s, and as early as 1931, the Manchurian Incident was sparked in part by Colonel Ishiwara Kanji’s belief that the area’s resources would be critical in winning a “final war” with the United States and uniting all of Asia. Matsuoka’s declaration above serves as an indication of the ideology’s centrality to official policy, but many have argued – in light of the actual implementation of the Co-Prosperity Sphere – that Pan-Asianism’s main use was as hollow rhetoric; the ideal diplomatic language to cultivate support for the Japanese empire.

Further complicating the picture of Japanese decision-making with regard to expansion in the 1930s were the competing strategies of the army and navy. Where the former pushed for a “northern advance” (hokushin-ron) into Manchuria and the Soviet Union, the latter preferred a “southward advance” (nanshin-ron) into the South Seas and the resource-rich colonies of the Dutch East Indies and British Malaya. Both posed their own challenges, and even within the service branches, there were disagreements over the specific details of the advance. Each plan demanded further spending on the respective service, which would be shouldering the bulk of the expansion efforts, and there was the constant fear that escalation would lead to an overstretching of resources at a time when Japan still relied heavily on the maintenance of trade relations.

Of course, we must not forget that all this strategic debating and conceptualizing took place in an international situation that was constantly in flux. Japan’s isolation after the invasion of Manchuria and its subsequent departure from the League of Nations were crucial factors in the resurgence of the hokushin-ron and nanshin-ron doctrines in official discourse. The war in Europe and Operation Barbarossa presented new opportunities and dangers for military planners and diplomats, whilst the final decision to wage war with the United States and Britain took into account the “quagmire” of the ongoing conflict in China. Nor was there a dictator who dominated the decision-making processes in the same way Hitler and Mussolini did; Emperor Hirohito’s role in Japan’s war planning remains a contentious topic in the overall historiography. On a related side note, the plurality of decision-making within Japanese interwar politics is always worth keeping in mind throughout studies of the period. Imperial Japan is often considered a “revisionist” power in the 1930s in the same way Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy are, but to apply the “fascist” label is perhaps going a step too far. As Robert Paxton claims:

Though the imperial regime used techniques of mass mobilization, no official party or autonomous grass-roots movement competed with the leaders. The Japanese empire of the period 1932-1945 is better understood as an expansionist military dictatorship [sic] with a high degree of state-sponsored mobilization than as a fascist regime.

In sum, the latter half of the interwar period for Japan was a period of great flux, both domestically and abroad. Militarists rose, though in a gradual and non-linear manner, to greatly influence the government, departures from internationalism and cooperation left the country searching for its place in a post-Depression global order, and the democratic ideals of the Taishō period came under fire from the challenge of ultranationalists, right-wing intellectuals, and the Young Officers. Multicausality, it would appear, is the watchword for students of Imperial Japan’s expansion in the 1930s.

Conclusion

When Prime Minister Katō Takaaki remarked in May 1925 that “The Japanese people… must come together in a grand resolution and effort to build the foundations for a new Japan,” it was a time of great yet seemingly contradictory changes in the Taishō state. Just a month before Takaaki’s declaration, the National Diet passed the Peace Preservation Law, enabling authorities to punish those who attempted to alter the national polity (kokutai) or threaten private property with up to ten years of imprisonment. That same day, the IJN’s newest carrier Akagi was launched at the Kure Naval Arsenal, converted from her initial battlecruiser design in accordance with the Washington Naval Treaty. Just weeks before Takaaki’s statement, the Diet also passed the General Election Law, enabling Japan to achieve universal male suffrage and advance towards greater democratization. Alongside these laws, War Minister Ugaki Kazushige had pushed through a new wave of army reductions, cutting the IJA’s force by four divisions.

In orthodox narratives of 1925, the Peace Preservation Law overshadows the achievement of universal male suffrage; the army and navy’s reduction is portrayed as a “holiday” from the previous devotion to armaments. As Dickinson puts it:

Our treatment of interwar disarmament privileges voices of dissent, not support. Japan agreed to naval ratios in the 1920s, but not without serious questions raised about the fairness of Japan’s numbers. Ground force reductions sailed through, but not without significant modernization of the Imperial Army and militarization of Japanese society… This story of dissent leads us effortlessly to the tale of disaster in the 1930s.

Hindsight, as this article has shown for other elements of interwar Japan, predisposes us to view the Taishō-era reforms as mere “experiments” in democracy, with the “collapse” of the system in 1931 facilitating the dramatic return of authoritarian governance and imperial expansion. Viewed from the “Dark Valley” of the 1930s, the themes which characterized Japan in the 1920s – democracy, internationalism, liberalization – appear as fleeting trends, efforts by Japanese politicians and society to mirror the global fashion. In the words of Kenneth Henshall, the pattern of the Taishō period was “advances for democracy and liberalism…invariably counterbalanced and checked by authoritarianism and expression.” As a convenient metaphor, “two steps forward, one step back” aptly describes the experience of the post-war decade in Japan from the vantage point of 1931 or 1941.

Instead, if we adjust our lens to view the developments of the 1920s as the product of a post-war global reordering, then the construction of a “New Japan” emerges as a viable narrative to follow. Arms reductions appear not as efforts undertaken solely for the sake of abiding by treaties with contested terms but as attempts to forge a crucial pillar of the new world order, in which disarmament and multilateral diplomacy earned one’s nation a place at the table of great powers. Taken as such, the rise of militarism and the ultranationalist “swing” appears not as an inevitable return to the pre-Taishō authoritarianism but rather as a direct challenge to the more liberal visions of a “New Japan” and perhaps as a response to the perceived decline – or purity – of the kokutai. The descent to war in the 1930s and 1941 appears not as a linear consequence of foreign aggression and exclusively imperialist designs but as deliberate choices made in response to and in pre-emption of regional security concerns – economic, political, and ideological. The “Greater East Asia War” was not the preordained endpoint of Japan’s post-World War I trajectory but a consequence of domestic and foreign factors which influenced the decisions of the interwar period. In the domestic sphere, the gradual and incomplete shift from liberal internationalism to ultranationalist militarism which marked the transition from Taishō to Shōwa characterized the struggle to redefine Japan’s image at home. Simultaneously, the escalation of hostilities from bilateral to multilateral war in the 1930s was a response to the circumstances faced – real or perceived – by Tokyo at critical junctures of its foreign policy.

All of this is to conclude with the key takeaway that the histories of Japan in the interwar period must be framed not by the tragedy and destruction of the World War, which ended it but by the contemporary attitudes and larger picture which emerged from the Great War that began it. Let us continue to write about the voices of dissent and opposition to the changes of the Taishō era without assuming their inevitable and effortless triumph in the Shōwa. In lieu of privileging the narratives of people and policies that would lead Imperial Japan to war in the 1930s, let us shed light on the stories of those who constructed a “New Japan” in the peace of the 1920s. Let us rethink the fatalism so common in accounts of Japanese interwar politics and avoid falling into the trap of smooth linearity in Japan’s expansionist path. By viewing Japan’s interwar years as a period of socio-political flux, historians can better understand how the post-war order witnessed a contest to reshape a “New Japan,” molded in response to both domestic and international trends. The ultimate triumph of the militarists and ultranationalists in this contest, as this article has attempted to show, was far from preordained when the reign of Taishō gave way to the era of Shōwa.

Bibliography

Asada, Sado. From Mahan to Pearl Harbor: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2013.

Asada, Sadao. “The Japanese Navy’s Road to Pearl Harbor, 1931-1941.” In Culture Shock and Japanese-American relations, edited by Asada Sadao, 137-173. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2007.

Barnhart, Michael A. Japan Prepares for Total War: The Search for Economic Security, 1919-1941. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University press, 1987.

Barnhart, Michael A. “The Origins of the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific: Synthesis Impossible?” Diplomatic History 20, no. 2 (1996): 241-260. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24913378.

Beasley, W. G. Japanese Imperialism, 1894-1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Best, Antony. “Imperial Japan.” In The Origins of World War Two: The Debate Continues, edited by Robert Boyce and Joseph A. Maiolo, 52-69. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Bix, Herbert P. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

Dockrill, Saki. “Hirohito, the Emperor’s Army and Pearl Harbor.” Review of International Studies 16, no. 4 (1992): 319-333. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20097309.

Best, Antony. “Imperial Japan.” In The Origins of World War Two: The Debate Continues, edited by Robert Boyce and Joseph A. Maiolo, 52-69. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Dickinson, Frederick R. World War I and the Triumph of a New Japan, 1919-1930. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Dickinson, Frederick R. “Toward a Global Perspective of the Great War: Japan and the Foundations of a Twentieth-Century World.” The American Historical Review 119, no. 4 (2014): 1154-1883. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43695889.

Drea, Edward J. Japan’s Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall, 1853-1945. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

Emperor Hirohito, “Declaration of War Against the United States.” December 8, 1941. From Gilder Lehrman Institute. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/japan-declares-war-1941.

Five Ministers Conference, “Fundamentals of National Policy.” August 7, 1936. In Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in World War II: Selected Readings and Documents, edited by Joyce C. Lebra. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Goto-Jones, Christopher. Modern Japan: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Hane, Mikiso and Louis G. Perez. Modern Japan: A Historical Survey. 5th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2013.

Hanneman, Mary. Japan faces the World, 1925-1952. Essex: Pearson Education Limited, 2001.

Harries, Meirion and Susie Harries. Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army. New York: Random House, 1991.

Hatano, Sumio and Sadao Asada. “The Japanese Decision to Move South.” In Paths to War: New Essays on the Origins of the Second World War, edited by Robert Boyce and Esmonde M. Robertson, 391-400. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

Henshall, Kenneth. A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. 3rd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Hotta, Eri. Pan-Asianism and Japan’s War, 1931-1945. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Humphreys, Leonard A. The Way of the Heavenly Sword: The Japanese Army in the 1920’s. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995.

Iida Yumiko. “Fleeing the West, Making Asia Home: Transpositions of Otherness in Japanese Pan-Asianism.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 22, no. 3 (1997): 409-432. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40644897.

Iriye, Akira. Japan and the wider world: from the mid-nineteenth century to the present. London: Longman, 1997.

Iriye, Akira. Pearl Harbor and the Coming of the Pacific War: A Brief History with Documents and Essays. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

Iriye, Akira. The Origins of the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific. Essex: Longman, 1987.

Kawamura, Noriko. “Emperor Hirohito and Japan’s Decision to Go to War with the United States: Reexamined.” Diplomatic History 31, no. 1 (2007): 51-79. https://www.jstor.o rg/stable/24916020.

Kawamura, Noriko. “Wilsonian Idealism and Japanese Claims at the Paris Peace Conference.” Pacific Historical Review 66, no. 4 (1997): 503-526. https://www.jstor.o rg/stable/3642235

Large, Stephen S. “Oligarchy, Democracy, and Fascism.” In A Companion to Japanese History, edited by William M. Tsutsui, 156-171. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing, 2009.

Lauren, Paul Gordon. “Human Rights in History: Diplomacy and Racial Equality at the Paris Peace Conference.” Diplomatic History 2, no. 3 (1978): 257-278. https://www.jstor.or g/stable/24909920

Lebra, Joyce C. ed. Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in World War II: Selected Readings and Documents. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1975

Marks, Sally. The Illusion of Peace: International Relations in Europe, 1918-1933. London: Macmillan, 1987.

Matsuoka, Yōsuke, “Proclamation of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” August 2, 1940. In Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in World War II: Selected Readings and Documents, edited by Joyce C. Lebra. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Matsuura, Masataka.”Japan and pan-Asianism.” In The International History of East Asia, 1900-1968, edited by Antony Best, 81-98. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Mauch, Peter. “Asia-Pacific: The failure of diplomacy, 1931-1941.” In Politics and Ideology, ed. Richard Bosworth and Joseph Maiolo, 253-275. Vol. 2 of The Cambridge History of the Second World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Nish, Ian. Japanese Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2002.

Orbach, Danny. Curse on this Country: The Rebellious Army of Imperial Japan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017.

Paine, S. C. M. The Wars for Asia, 1911-1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Patalano, Alessio. “Feigning grand strategy: Japan, 1937-1945.” In Fighting the War, ed. John Ferris and Evan Mawdsley, 159-188. Vol. 1 of The Cambridge History of the Second World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Peattie, Mark R. “Nanshin: The ‘Southward Advance,’ 1931-1941, as a Prelude to the Japanese Occupation of Southeast Asia.” In The Japanese Wartime Empire, 1931-1945, edited by Peter Duus, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, 189-242. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Saaler, Sven. “The Military and politics.” In Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History, edited by Sven Saaler and Christopher W. A. Szpilman, 184-198. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Schencking, Charles J. Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, and the Emergence of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868-1922. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

Schencking, Charles J. “The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Constructed Consciousness of a South Seas Destiny, 1872-1921.” Modern Asian Studies 33, no. 4 (1999): 769-796. https://www.jstor.org/stable/313099.

Sheftall, M. G. “An Ideological Genealogy of Imperial Era Japanese Militarism.” In The Origins of the Second World War: An International Perspective, edited by Frank McDonough, 50-66. London: Continuum, 2011.

Shilllony, Ben-Ami. Revolt in Japan: The Young Officers and the February 26, 1936 Incident. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Shinichi, Kitaoka. From Party Politics to Militarism in Japan, 1924-1941. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2021.

Shinichi Kitaoka, “The army as a bureaucracy: Japanese militarism revisited.” In Politics in Japan, 1931-1945, ed. Antony Best, 243-260. Vol. 1 of Imperial Japan and the World, 1931-1945. London: Routledge, 2011.

Shinichi, Kitaoka. The Political History of Modern Japan: Foreign Relations and Domestic Politics. Translated by Robert D. Eldridge and Graham Leonard. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Shoji, Jun’ichiro. “What Should the “Pacific War” be Named? A Study of the Debate in Japan.” NIDS Journal of Defense and Security 12 (2011): 46-81. http://www.nids.mod .go.jp/english/publication/kiyo/pdf/2011/bulletin_e2011_4.pdf.

Steiner, Zara. The Lights that Failed: European International History, 1919-1933. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Swan, William L. “Japan’s Intentions for Its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere as Indicated in its Policy Plans for Thailand.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 27, no. 1 (1996): 139-149. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20071764.

Tipton, Elise K. Modern Japan: A social and political history. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Yellen, Jeremy. The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere: When Total Empire Met Total War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Image Bibliography

Chaen, Yoshio. “Zusetu 2/26 Jiken.” Nihon Tosho Center. 2001. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:226_Returning_Troops.JPG.

“Jap[anese] peace delegates.” Bain News Service. 1920. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014709002/.

“A scene of the Imperial General Headquarters meeting, 29 April 1943.” Asahi Shimbun. 1971. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Imperial_general_headquaters_meeting.jpg.

“War Flags of China obtained by Japanese forces in Nanking, December 14, 1937.” Asahi Shimbun. 1938. China Incident Photograph Album Volume 2(Shina Jihen Shashin Zenshu Vol. 2). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:War_Flags_obtained_by_Japan_in_Nanking.jpg.